For the business professional, leadership development is a foundation of organisational success. Around the globe, companies invest billions into cultivating the leaders of tomorrow through bespoke coaching sessions and executive education programmes. In 2019 alone, global spending on leadership development reached an estimated $366 billion—a testament to its perceived importance.

Yet, despite this significant investment, the results are varied. Organisations frequently encounter difficulty in seeing tangible changes in leadership behaviour or notable improvements in team performance. Employees often voice frustrations over inconsistent or ineffective leadership, and leaders themselves report feeling overwhelmed or unprepared. This growing dissatisfaction signals that traditional methods of leadership development may fall short of delivering the anticipated value.

The root of this issue lies in the common belief that leadership is simply a collection of personal traits or skills that can be developed independently. The industry often centres on building individual capabilities—such as enhancing confidence, communication, decision-making, or strategic vision. While these skills are undoubtedly beneficial, an overemphasis on personal growth risks neglecting a crucial component of leadership success: the environment in which leaders are expected to perform.

Behaviour in Context: A Broader Perspective

Source: medium.com

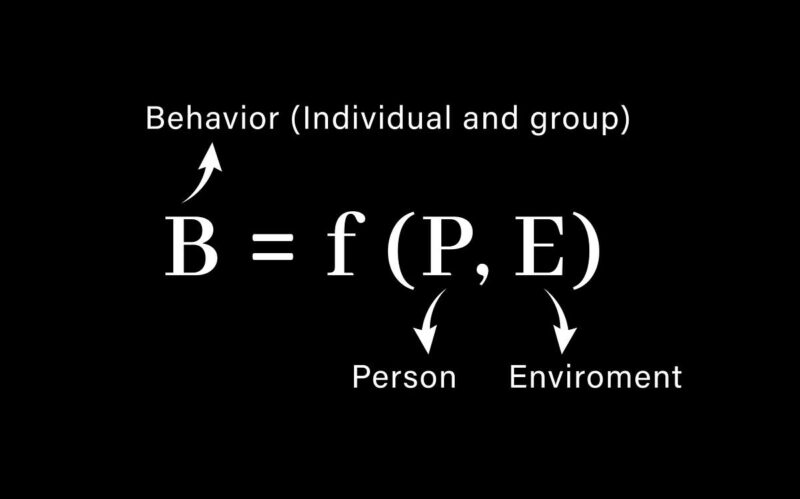

Decades past, psychologist Kurt Lewin introduced a profound yet straightforward formula: B = f(P, E). This equation posits that behaviour (B) is a function of the person (P) and their environment (E), challenging the notion that human actions are solely shaped by internal characteristics. It implies that a person’s surroundings—social, structural, and cultural—play an equally pivotal role in influencing behaviour.

In the context of leadership development, Lewin’s insight is timely and instructive for business professionals. Companies must no longer regard leadership as something inherent solely within individuals. The culture, systems, and team dynamics surrounding leaders should also be taken into account. Focusing only on the individual while disregarding the environment is akin to teaching someone to swim in a pool without water.

Leadership does not exist in isolation. It manifests within teams, departments, and specific organisational frameworks. It is swayed by role clarity, access to resources, decision-making norms, psychological safety, and numerous other contextual factors. Investing in aligning these conditions with desired behaviours increases the chances of successful leadership development.

Shifting Focus from Individuals to Interactions

For business professionals, team-level interactions offer a potent area of focus. Teams are the motors of organisational tasks, where strategies are implemented, innovations take root, and culture is palpably experienced. They also represent the immediate environment where most leadership takes place.

Often, leadership development removes participants from their actual teams, whisking them away to workshops, 360-degree feedback exercises, or simulation-based assessments. While these yield useful insights, returning to environments with misaligned expectations, unclear responsibilities, or strained interpersonal dynamics can diminish much of the learning.

Conversely, development efforts that embed within the leader’s real team environment are more likely to persist. This entails shifting some focus from the individual leader to the broader team dynamics. Questions like “Is this team’s purpose clearly defined?” or “Do team members feel safe voicing concerns?” can be just as crucial as “Is the leader a good communicator?”

Designing an effective team environment requires attention to practical elements. Are team roles and responsibilities clearly articulated? Is alignment present between team goals and organisational priorities? Do team members have consistent opportunities to reflect on working together, not just on deliverables? Are the appropriate processes established to aid coordination, decision-making, and mutual accountability?

When these foundational aspects are established, leaders need not rely solely on charisma or effort to drive performance. Instead, they function within a system that supports their role, magnifies their strengths, and facilitates shared leadership across the team.

Leadership as a Collective Endeavour

Source: tpd.edu.au

For business professionals, it’s essential to understand that leadership is a collective function, often distributed across team members rather than concentrated within a single figurehead. In top-performing teams, multiple individuals may lead at different times, depending on the task or required expertise. This flexibility enhances team adaptability, resilience, and creativity.

Nevertheless, distributed leadership doesn’t occur automatically. It must be cultivated in environments that encourage initiative, nurture peer feedback, and value collaboration over hierarchy. Leaders, in this context, assume a facilitative role within the system rather than being the focal point. Their job is to establish clarity, build trust, and foster conditions where others can also lead.

This has significant implications for senior leadership teams, responsible for cross-functional alignment and strategic clarity. Without a well-structured team environment, they can succumb to siloed thinking or interpersonal rivalry. By prioritising team operations—clarifying shared goals, encouraging open dialogue, and investing in team-level reflection—organisations can enhance cohesive and effective leadership at the top.

Reimagining Leadership Development as Systemic Reform

For business professionals, this perspective requires a transformation in how leadership development is approached.

First, organisations must approach leadership growth as a system-wide intervention, not an isolated process. This involves training individuals while redesigning teams, adjusting workflows, and reconsidering reward structures that inadvertently reinforce undesirable behaviours.

Second, development programmes should integrate with real work. Leaders should apply new insights directly within their teams, with support for experimentation, reflection, and adaptation. Coaching can extend beyond individuals to teams, helping groups understand their dynamics and practice new collaboration methods.

Third, leaders should develop in their context—equipped not only with new tools but also supported in diagnosing and enhancing the systems they impact. This necessitates time, attention, and a willingness to probe difficult questions about organisational operations.

Finally, success metrics must evolve. Rather than relying solely on participant satisfaction or pre/post self-assessments, companies should gauge changes in team performance, collaboration quality, and cross-functional effectiveness—true indicators of successful leadership development.

Conclusion: Crafting Environments for Leadership, Not Just Developing Leaders

Source: itnetwork.rs

The time has come for business professionals to reconsider how leadership is developed. The traditional model—focusing solely on personal improvement—is inadequate in an era characterised by complexity, interdependence, and rapid change. Effective leadership transcends mere personality or persuasion; it is a product of context, culture, and collaboration.

By shifting focus from individual transformation to environmental design, conditions are created where leadership can genuinely thrive. This approach leads to more resilient teams, engaged employees, and adaptable organisations—not by altering leaders in isolation, but by transforming the environments that mould them.